Origins of Female Malay Education

Singapore has largely achieved parity in education between males and females today, but this was not really the case in early post-war Singapore. As we dedicate the year 2021 as the Year of Celebrating SG Women, let’s not forget that a century ago our women faced difficulties in many areas that we would take for granted today.

This 5-part series was originally written as an assignment for a Malay Studies module at NUS in late 2017. I thought it was a good idea that I revisit this article as the term intersectionality gained traction since the General Elections last year. This term refers to a framework for understanding how individual characteristics like gender, ethnicity, language or social class can overlap with one another. Within systems of power these characteristics may create connecting experiences that either oppress and advantage people in the workplace and broader community.

There is limited literature on the development of Malay education in Singapore, especially in the area of girls’ education. Most academics and writers choose to focus on the development of the education system in general instead, which revolved around changes caused by turbulent social movements on the 1950s. Little is mentioned on how these changes brought an increasing trend of female education in schools. That said, research done on the macro-processes during this period, i.e. reforms to the Singaporean education system, Malay nationalism and the social discourse on women’s rights, is plenty. Their actors (social organisations and politicians) makes good representation as intermediaries between the colonial/post-colonial state and the Malay community. This post hence aims to look at how the colonial education system and discouraging social attitudes back then prevented Malay women from receiving education like how their male counterparts did, explore the factors that created favourable conditions for Malay girls to attend school, and how the situation has improved since.

Historical Development

Modern, secular Malay education first started in the Straits Settlements in Penang in 1816 as the Penang Free School. The first girls’ school for the Malays was added in 1817 in the same school compound. Several new Malay girls’ schools were then established in the next century throughout the peninsula, but they were often closed within a few years of establishment due to poor attendance and teaching staff.

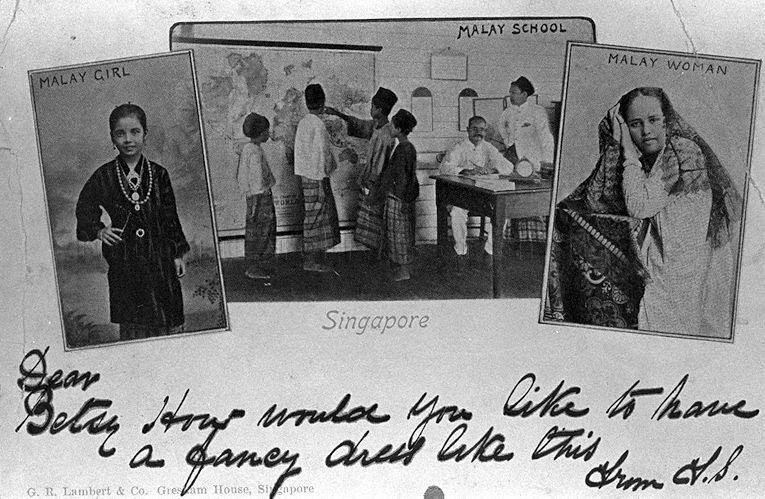

In Singapore, the first Malay girls’ school was established at Telok Blangah in 1884. Similar to the situation shared by schools on the peninsula, the local Malay girls’ schools faced problems in enrolment and teaching staff. According to interviews and research, the main objections against female education amongst the Malays was the fear that their daughters will be traversing streets unaccompanied and their increased literacy may lead to unintended romances because they could start writing letters to potential “boyfriends”. There were also suspicion that their children will undergo religious conversion in the girls’ schools opened by Christian missionaries. The enrolment of Malay girls at the turn of the 20th century was hence only 1% to 2% in the Straits Settlements.

It was revealed that the perception that Malay women ought to stay in the kitchen was common amongst parents, and reports published by the British educators noted that cookery and needlework actually could have been learnt from their mothers at home instead. Teaching staff for these Malay schools were extremely inadequate during the pre-war years, while insufficient accommodation in girls’ schools also meant that the girls had to attend co-education instead, a phenomenon that caused uneasiness in many Malay parents. Such uneasiness was also acknowledged in the Colony’s reports.

Despite the difficulties in establishing a stronger foundation for Malay girls’ education, there were efforts to promote Malay women to be literate in the community. Young Muslim intellectuals like Syed Shaikh Al-Hadi and Ahmad Lutfi, who represented a younger, progressive Islamist movement in the community, critically led the discourse on the importance of education for women. They argued that progress in society and women was to be attained by study and the acquisition of knowledge. Malay female educators like Hajjah Zain and Siti Mariam, editors of Bulan Melayu and Kencana respectively, published articles to stress the importance of the role of education as well. However most advocated that women’s education should emphasise religion, handicraft and domestic skills, as she is the mother and first educator of her children.

While the enrolment for Malay women only made slight increments over the decades leading to the war, the aristocratic Malay families and Malays employed in the Malayan Civil Service and teaching sectors were greatly influenced by the British who were in favour of female education. At the same time, the British attempted to improve the quality of education for Malay girls. In 1918, the first Lady Supervisor of Malay Girls Schools was appointed. Enrolments rose as she adapted the curriculum to fit Malayan needs and initiated training classes for Malay teachers. Regrettably, economic pressure led to the retrenchment of this post in 1933.

As of 1945, there were seven Malay girls’ schools in Singapore and fourteen “co-educational” ones. The so-called “co-educational” schools were in fact just Malay boys’ schools that also accepted female students because of proximity and lack of accommodation in other girls’ schools.

It is important to note however, that the British policies dealing with Malay education were meant to fit students for a career in peasant agriculture. The school curriculum for girls included handicraft, sewing, cooking and basketry. Malay vernacular schools did not teach English and did not extend beyond primary school.

World War II led to significant changes in the Malay community. For the first time, women had to lead the household because for many, their husbands and fathers either died or left home. They realised that their illiteracy kept them disadvantaged and this became an incentive to pursue education for their daughters post-war. During the occupation, the Governor of Kedah, Sukegawa Seiji, urged Malay women to be emancipated from their status “as mere chattels of their men”. A social discourse on women’s rights to education gradually emerged. At the same time, nationalism bloomed amidst rising awareness amongst the Malays about their economic disadvantages and political vulnerability as compared with the immigrant communities. Social and political turbulences of the post-war period also pushed for reforms in the education system. These factors will be discussed in greater detail in the next few posts!